We need to talk about your grades.

Dear Kids,

We need to talk about your grades. Like many other things in life, they’re not going to look or feel like anything you’re used to for the next few months. You could work really hard, or choose to slack off, and still end the semester with the same word on your report card: Credit. It might not feel fair. Or it may be a relief.

Dear Kids,

We need to talk about your grades. Like many other things in life, they’re not going to look or feel like anything you’re used to for the next few months. You could work really hard, or choose to slack off, and still end the semester with the same word on your report card: Credit. It might not feel fair. Or it may be a relief.

A former student of mine rang up my groceries at the market a few weeks ago. “I heard,” she said conspiratorily, “that we’re not even going to get any grades for the work we did. But I worked so hard on it! Is it going to stay like that for the rest of the year?!” This was followed by one of her signature eye rolls and an exasperated plop of cheese crackers into my grocery bag.

I agree, it’s awful to feel like no one will acknowledge the caliber of hard work you’ve done. It’s especially tough when that work required immense self-discipline, because it would have been easier to lose yourself in social media all day. You probably know people who did exactly that- and no, there will be few repercussions for their actions (or lack thereof). You are not old enough to be rewarded with a promotion at work, or a fat bonus at the end of an especially profitable quarter. Grades may feel like the one sort of “payment” you receive for your efforts. Now, we’ve taken that away.

You and your teachers have operated within a social contract for years, ensuring that we would do our best to dole out grades that fairly and honestly reflected the quality of work you turned in. Being fair is really important to us. Some of your teachers are conflicted by our new “no grades” policy too.

Grades can feel like our tiny way to promote justice in a world that doesn’t operate according to our rules.

We like rewarding your hard work with terrific grades. We rejoice when we watch you apply yourself and see your scores rise as a result. Even failing grades- though they don’t feel good- serve a purpose. Low marks can be our last straw at communicating to students and their families. At our best, failing grades say, “We see you. What you’re doing and what we’re doing isn’t working. Let’s make changes.” At our worst- teachers are humans too- the message may be more like, “I worked really hard to teach this class, and you worked really hard to ruin my efforts. You earned this.” For students that are highly capable, and only taking home Cs on their report cards, a certain message is also begging to be heard.

Traditional grading systems refereed most of our own schooling and that of your parents. As the authors of A School Leader’s Guide to Standards-Based Grading (2014) explain, letter grades are a widely accepted shorthand for communicating students’ success. In middle and high school, your teachers may have upwards of 150 students on their roster; this “shorthand” is far more efficient than an in-depth conversation with every family. In issuing letter grades, we’re carrying on a tradition that feels familiar, efficient, and fair. You might feel frustrated that this familiar give-and-take has been upturned; rest assured that many of your teachers share that same sentiment.

But I wonder if this pause on grading could get us to ask some deeper questions:

What if your only job was to learn? And what if our only job was to make sure that it happens?

Learning has very little to do with completing assignments or scoring 70% or higher on exams. And teaching well is not the same as grading assignments. Scores and percentages are very practical ways for adults to measure your learning- many of you will even encounter similar assessments in your adult life. They are not, however, the point.

Let’s think instead about learning that makes changes in how you understand the world, and what you’re able to do in it.

This includes learning how to navigate life in the company of others, whether you sit by them in school or share the virtual space in a Zoom meeting. Discovering new things that you find beautiful, following your own path of curiosity, enjoying a nurturing space to create new things: that’s the kind of learning that doesn’t stop after 12th grade. Thank goodness! It’s also the kind of learning that inspired many of your teachers to throw themselves into the challenging career of education.

Here’s something worth thinking about: by the time your teacher enters a grade into a progress report or report card, you already had a pretty good idea of what that grade would be. Research suggests that most students are 80% accurate at estimating their own grades (Kuncel, Crede, & Thomas, 2005). In other words, you tend to know what’s expected of you, and how well your work fits within those expectations. This may or may not ring true with your own experience- such is the nature of research- but the trend has been confirmed with over 80,000 students (Hattie, 2009). Our grades are telling you how well you fit within the parameters we created. That might reflect learning, and it might not.

Striking the right balance between ethics and accuracy, in a profession made up of adults who love young people and want to see them succeed, is a tricky thing. We want you to learn. We want you to feel supported. We want you to know when you’re not quite there yet. Behavior, effort, and attendance often influence a student’s final grade in conjunction with measures of their achievement (O’Connor, 2011). There is also real reason to place value on the 21st century skills that go beyond school. We are constantly trying to to our best- but authentically knowing what’s most important to measure learning, and the best way to guide 150+ individuals on that path without losing work-life balance ourselves, is a challenge.

What we do know for sure is that the clearer you and your teachers are about what it is you’re supposed to learn, the better the chances are that you’ll learn it (Hattie, 2009). This clarity is different from knowing that if you read six chapters of a book, and complete all the reading comprehension questions, you’ll get an A. It’s more like understanding from the get-go that you’re going to learn how an author creates a coherent theme, and knowing that when you’ve learned it when you can predict how a theme would change if a book ended differently. Contributors to the world of academia describe these clear things you need to learn as learning intentions, and evidence of how well you’ve learned it success criteria. Those aren’t phrases that roll of the tongue, per-se, but there are volumes written about how essential they are to learning. They give us much more to think about than, “Did I get an A?”

If for this time period you don’t have grades to measure your success, consider a personal reflection: What am I supposed to be learning here? How well have I learned it?

Moreover, if you don’t need to worry about good grades right now, there’s more reason than ever to pay attention to feedback. Your teacher might be offering feedback to the whole class during a virtual meeting, or putting some serious time into adding comments to your works-in-progress. That feedback required significant focus from your teacher, and he did it because he knows that timely, appropriate feedback can double your rate of learning (Hattie, 2019). It can give you a clearer picture regarding the difference is between your current learning status, and how far he expects you to rise. Getting into the habit of seeking out, and responding to, feedback, is a skill that will enrich your learning and your work for a lifetime (Dunning, 2014).

A colleague of mine recently lamented that if she was grading during distance learning, she was only grading privilege. In a time of unprecedented social upheaval, I couldn’t agree more. When I see students balancing the demands of caring for their siblings, food insecurity, and a shared anxiety about the future, the least “fair” thing to do is to assign them grades. But if your family situation allows you to maintain high academic expectations, now is the time to use what we know about how learning works, and have a some fun with it. Get really clear about what it is you’re supposed to learn. Seek honest feedback about where you are in your learning, without fear that it will sink your grade.

Since so many of our schools are on hiatus from a grading system that has hardly changed since the industrial revolution (O’Connor, 2011), perhaps now is the time to take a fresh look at learning. How does it interest us? Where could it take us? How do we do it better? Your learning habits impact you more than anyone else, and we can’t put a grade on that.

References:

Hattie, J.A.C. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of 800+ meta-analyses on achievement. London: Routledge.

Hattie, J., and Clarke, S. (2019). Visible Learning Feedback. New York: Routledge.

Helfebower, T, et. al (2014) A School Leader’s Guide to Standards-Based Grading. Indiana: Marzano Research.

Kuncel NR, Credé M, Thomas LL. The validity of self-reported Grade Point Averages, class ranks, and test scores: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Rev Educ Res. 2005;75: 63–82.

O’Connor, K. (2011). A Repair Kit for Grading (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Sheldon, O. J., Dunning, D., & Ames, D. R. (2014). Emotionally unskilled, unaware, and uninterested in learning more: Reactions to feedback about deficits in emotional intelligence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(1), 125–137.

Sticca, Fabio et al. “Examining the accuracy of students' self-reported academic grades from a correlational and a discrepancy perspective: Evidence from a longitudinal study.” PloS one vol. 12,11 e0187367. 7 Nov. 2017.

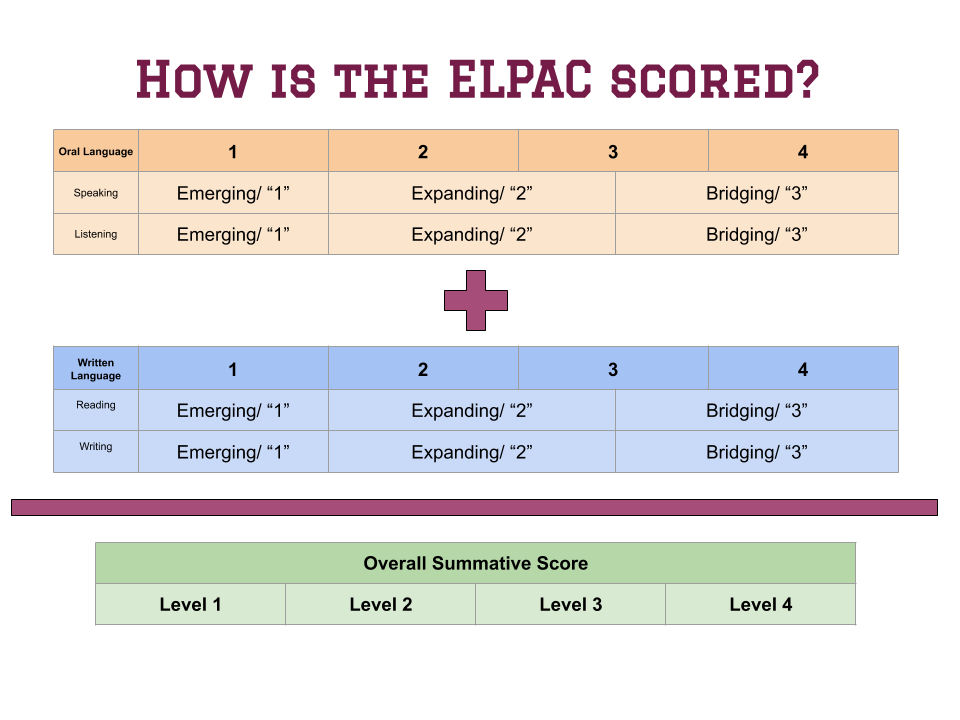

How the ELPAC is Scored

Two years after its inception, scoring for California’s state language assessment- the ELPAC- remains mysterious for the people it impacts the most: students. The past decade of educational research reveals the overwhelming importance of clarity. Somehow, however, we’ve muddied the waters on an assessment that is often the gatekeeper for allowing middle and high school students to take an elective of their choice.

There was a joke years ago, that the TV show Family Guy was written by a bunch of manatees who swam around in a tank rearranging “idea balls” into episodes. Such was the randomness of the jokes and the abruptness of their cutaways. This writing style must not be a total fail, because the ol’ manatees are still hard at work, two decades after the show’s premiere. It’s a formula that works for comedy. It doesn’t work for kids.

Two years after its inception, scoring for California’s state language assessment- the ELPAC- remains mysterious for the people it impacts the most: students. The past decade of educational research reveals the overwhelming importance of clarity. Somehow, however, we’ve muddied the waters on an assessment that is often the gatekeeper for allowing middle and high school students to take an elective of their choice. Most middle schoolers I work with know that they need a “four out of four” to pass the ELPAC. How that four is actually calculated, on an exam with over fifty questions, is nonsensical to the average seventh grader. It might as well be written by a pool full of manatees.

Like most of the standardized tests I see in schools, the ELPAC assigns a scale score (i.e. “1482”) and a proficiency level (i.e. “somewhat developed”) to students’ performance. Overall proficiency levels correspond with a straightforward 1-4 number value. There’s more: students’ scale score is comprised of two language areas, oral language and written language, which each have their own scale score (anywhere from 1150-1950) and proficiency level (beginning/somewhat/moderately/well developed) and also correspond with a 1-4 number value. Are you still with me? The language areas are further divided into two domains each, which are given a level one through… THREE! If you’re confused, imagine what kind of sense this makes to an eleven year-old who speaks English as their second language. Or, try this conversation on for size:

Teacher: What score do you need to pass the ELPAC?

Student: Four.

Teacher: Awesome! Let’s set some goals. Which domain do you need to work the most on?

Student: Reading. I got a two last year. So this year, I’m going to try to get a four on the reading part.

Teacher: I like your thinking, but a three is the highest you can get on the reading domain.

Student: But I thought it was a scale of 1-4?

Teacher: It is 1-4. On the whole test. But not the domains. Domains are 1-3. The highest score you can get on the test is a four. Trust me.

I don’t have a clever solution. But I do have a picture! When too many of my conversations with teachers and students sounded like the one here, I put this together to help myself make sense of what I gathered from the California Department of Education, ELPAC.org, and startingsmarter.org.

I also have some advice: be honest, open, and patient. Trying to figure out how to pass a test is one thing, and learning is often another. Let’s keep learning at the core of our conversations with our kids.

Dropping the L-Bomb at School

By saying that I cared more, I started to care more. And if I sounded a little ooey-gooey in the process, so be it.

A few years ago, I accidentally told a student that I loved her. It was so weird. Mushy-gushy talk was not my M.O, despite the plethora of viral TED talks and motivational videos touting the importance of love when working in schools. “Kids will not care how much you know until they know how much you care”, and all that. Saying “I love you” at school felt weird before I even finished my sentence; it was like trying out a language that wasn’t mine. To confirm the absolute discomfort of it all, I heard another delightfully sarcastic student repeat the words under her breath to a friend, followed by “AWKward!” on her way out the door. They don’t mention that part in the TED talks.

This particular girl was an archetype with whom too many teachers are familiar: dyed black hair hanging in her face, trying on a new friend group every few months, often crumpled in the hallway over something that had upset her. She drew tragic angels in her sketchbook, and skulking anime characters who wept as they tangled their bodies together. She was one of those students whose deep well of needs, despite the attention of counselors and teachers and her peers, seemed bottomless. On that day, she was withdrawn about something new and refused to talk with anyone, even a counselor. I felt exasperated in my loss for words. So as she made her way out of my classroom at the passing period, I blurted out, “I love you and I just want you to be happy.”

I love you and I just want you to be happy? Could I have been more cliche? AWKward! is exactly what I would have said if her cynical classmate hadn’t rolled her eyes and done it for me. Besides that, love is a word I saved for my kids, my husband, my parents. You don’t muddle that kind of stuff with teaching teenagers how to write essays. It’s gross.

I treated the word love like a currency that could be worth more if I said it less. So, setting it loose with this one student, this one time, felt like invoking King Kong to tear his way through my classroom to show that I cared; it felt a little over-the-top. Climb down from the Empire State Building, Mrs. Miller. That is not the kind of thing you say at work. Or at least, it didn’t used to be.

The whole thing reminds me of a dear friend who went paddle boarding with me once: he spent the whole ride rigidly straining for balance, until he finally fell off the board at the very end of our trip. He was so astonished that falling in the water was not actually awful, that he wished he’d fallen in earlier so he could have had more fun. Likewise, stumbling over my own cheesy words that day, being mocked by a student who channeled my inner critic with precision, and feeling a little ridiculous, didn’t actually destroy all my credibility.

My compassionate word-blunder had an unexpected side effect: it unlocked the “do not touch” part of my vocabulary.

Things got worse. I began using the word love with all my classes. Even the rough ones. (On certain days, especially the rough ones.) To many of my students, it probably sounded silly- but I discovered that I relish being the person who is that kind of silly. “Love you guys, see you tomorrow,” became a routine sign-off at the end of class. Sometimes I even began with a “Good morning, love y’all, glad to see you… make sure you have something to write with today.” Yeah. That kind of hippy-dippy, touchy-feely fluffy language, paired with teachery get-out-your-school-supplies. It did not mean that I was overjoyed to see every student who walked into the room- there were 150 of them, and they were teenagers, and I am a mere mortal. But there was love there, and saying it seemed to make the sentiment more real.

Teachers have the uncommon privilege- and challenge- of setting the tone for culture among groups of thirty-plus at a time, multiple times a day, 180 days a year. In my classroom, the L-word happened a lot. I don’t know if my students felt it deeply or they wrote me off as a jolly-good person who just says that kind of thing to everyone. But I do know that the words I used had a powerful impact on the only countenance I can truthfully measure: mine. There is something to that “fake it ‘til you make it” adage; by May, I can honestly say that I really loved my job- and my students- more than any other year in the classroom.

I must report that telling my classes that I loved them wasn’t a cure-all, for my students or for me. It did not endow me with the zen to withstand every single sling and arrow that middle schoolers throw. And I doubt that my instruction improved or that students became better readers and writers just because I let the word love fly around the room like a class pet. No one threw their arms around me and said, “Thank you! It’s just what I needed to hear!” But by saying that I cared more, I started to care more. And if I sounded a little ooey-gooey in the process, so be it.

So I’m grateful for the student that finally got me to talk about love, however awkward it sounded. Love is only a limited commodity if we make it so.

You're an Orchestra, Not A Violin: Collective Teacher Efficacy

I was witness to the collective efficacy cycle, set to the tune of cellos and violins.

If you’re an orchestra teacher, please forgive me, in my exuberance, I’m bound to word something wrong here. I am not a trained musician or a music teacher, but I believe we have a lot to learn from strings class.

Just before school let out for winter break, my help was requested in fifth period orchestra. This request came at the height of year end busy-ness: district meetings, state mandated reports, grading deadlines, and general widespread restlessness in our middle schoolers. Moreover, some of the most intelligent, dedicated teachers I work with had recently intimated that they worried they were spinning their pedagogical wheels- trying to “make it work” but starved for time and collaboration, or even confirmation that they were headed in the right direction. There was a sense that we were working alone, en masse, trying to keep up.

My musical training peaked when I learned to play Hot Cross Buns on the recorder. Thus, like anyone with a Masters in education, my fallback plan for orchestra class was self-depricating humor. Yes, I planned to tell the students, it is true that even though I’m your guest teacher, I don’t know what that instrument is called or how you’re supposed to hold it. Is that how it’s supposed to sound? Bravo! Play on! Our fifth period strings class, however, had something else in store. Over the course of an hour, they modeled exactly what I needed to be reminded of: collective efficacy in beautiful, living, action.

Collective efficacy is a term borrowed from the world of cognitive psychology. In the late 1970s, Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura (1977) noticed that there was a correlation between groups’ confidence in their abilities, and their actual performance. Simply put, groups who believed they will be successful, actually succeeded. This phenomenon has been observed in everything from volleyball teams (Spink, 1990), to neighborhood watches (Sampson, Rodenbush, & Earls, 2005), to- you guessed it- education (Goddard, Hoy, and Hoy, 2000).

In recent years, John Hattie plunked collective teacher efficacy onto the tip top of his effect size list, solidifying its place as the star upon the Christmas tree of instructional impact. “The New Number One”, as he called it, largely outweighed other effects such as socioeconomic background, classroom management, and even feedback. Understanding collective teacher efficacy, however, can easily veer into the realm of the abstract. It is not quite as straightforward as “Clarity” or “Goals”. There are lots of syllables, and it’s complete with a buzzword (efficacy) whose meaning might conveniently shift based on interpretation.

Here are a few ways orchestra students reminded me what it can look like:

Tuning takes a village

Before the students rehearsed their songs, one of them led the group in a tuning exercise. As the least musically-knowledgeable person in the room, I was mystified by the process. “C”, she would call out, and the whole room would move from silence to a searching, quivering “C” note. It was messy and also lovely. Amazingly, all the students seemed perfectly clear on what it should sound like when the whole ensemble tuned.

“But how do you know if you all have it right?” I asked. I’ve asked this question dozens of times, in learning walks with our staff. It’s a shorthand we borrow from McDowell’s Developing Expert Learners, to gage students’ orientation relative to success criteria. But in this case, I really wanted to know how they knew. Their answer gave me goosebumps.

Determining what kind of change we need to affect, and using a variety of ways to determine if we are making a difference, starts and ends with listening to what’s in the room.

“Our ‘c’ might sound a little different from another orchestra’s ‘c’,” they told me, “but that’s alright; each group will sound slightly different. We know by listening to each other - we could use a tuner, but we don’t need to.”

This group of teenagers had figured out precisely what the most effective school faculties already know. What counts as success in your school is uniquely defined by the students and teachers who are the school. Yes, there are standardized measures of proficiency to reference- just like tuners- but a group’s particular stories, strengths, and challenges will shape how the group defines and measures growth.

When we say “collective teacher efficacy”, an appropriate question is, “Efficacy doing what?” Just like an orchestra, one school’s “We did it!” will look slightly different from that of a school down the road. Determining what kind of change we need to affect, and using a variety of ways to determine if we are making a difference, starts and ends with listening to what’s in the room.

Feedback culture

“My” orchestra students rehearsed seven songs in my tenure. By the third song, I asked them, “What did you all do well there? What needed to be better?” It was an honest question, and I was entirely dependent on their expertise. The students were quick to shoot their hands in the air. “Speed!” a few of them volunteered, “We went too fast on one part and too slow on the others.”

I was witness to a collective efficacy cycle, set to the tune of cellos and violins.

“Is that something you can pay attention to in the next song?” I asked them.

“Yes!”

When the students wrapped up their next song, I asked, “how the speed that time?”

“Better! Yes, much better!” they agreed.

“What did you do differently? Do you think that’s something you could do again?” The kids enthusiastically bobbed their heads and turned their pages to the next song.

In a matter of minutes, this group of teenagers had identified a problem, worked together to fix it, analyzed the results, and agreed upon the outcome as a shared success. I was witness to a collective efficacy cycle, set to the tune of cellos and violins.

That kind of culture, in an orchestra or a school, takes time to cultivate. But it is well-worth the investment, and it is entirely possible. When my school started using meeting time to analyze student work and collectively tackle problems, our focus moved from that of compliance to real curiosity. At our best, like the orchestra students, we could revisit a problem with new evidence over time, to see if our changes were working. This culture of feedback and response requires vulnerability and collaboration, and it is vital for collective efficacy.

We can, because we did.

The orchestra students at my school have been consistently winning awards since the arrival of our full-time music teacher, three years ago. Many of them qualify for free or reduced lunch, we have a dwindling budget due to declining enrollment, and we’re not necessarily known as a “good” arts school. But these kids know they’re good. They have accolades proving that others know they’re good, too. Their own feeling of efficacy is based on experience.

Likewise, collective teacher efficacy is more than just decorating the staff lounge with lines from The Little Engine That Could. “We think we can, we think we can,” sounds very nice. It’s not for me. Real confidence comes from experience.

One of the best responses I’ve heard from a teacher was, upon seeing her students’ state test scores, “Hey, I worked really hard on getting them better at that- and look, it paid off!”

As an instructional coach, it is thrilling to see teachers’ hard work be validated. Seeing evidence that students learned more, as a result of teaching and reteaching and holding kids to high expectations, is reason to shine. And it gives us confidence that we can do it again.

Researchers Goddard, Hoy, and Hoy call this “Mastery Experience”, and they cite it as a critical component for building collective teacher efficacy. The confidence that, as a whole, we can cause significant learning- starts with evidence. Find the success story, and celebrate that accomplishment as a group. Like our orchestra students, we believe we can affect change if we know that we have affected change.

Witnessing the collective efficacy of orchestra students reminded me of the potential we have as teachers, to create something that is not only technically correct, but also beautiful. Learning and music are both, after all, a harmony of precision and artistry.

And the good news is this: we are not meant to be soloists. We’re in this together.

Look familiar? This post was also appeared on the website for my parter consulting group, The Core Collaborative. Check them out!

Sources/for further reading:

DeWitt, Peter. “How Collective Teacher Efficacy Develops.” Educational Leadership, vol. 76, 2019, ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/jul19/vol76/num09/How-Collective-Teacher-Efficacy-Develops.aspx

Donohoo, Jenni, et. al. “The Power of Collective Efficacy.” Leading the Energized School, vol. 75, no. 6, 2018, nlpslearns.sd68.bc.ca/documents/2018/09/collective-efficacy-article.pdf.

Goddard, et. al. “Collective Teacher Efficacy: Its Meaning, Measure, and Impact on Student Achievement.” American Educational Research Journal, vol. 37, no. 2, 2000, citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.123.9261&rep=rep1&type=pdf

“Collective Teacher Efficacy (CTE), According to John Hattie.” Visible Learning.org, visible-learning.org/2018/03/collective-teacher-efficacy-hattie/ Accessed 4 January, 2020.

McDowell, Michael. Developing Expert Learners. Corwin, 2018.

What twelve year-olds can teach you when you give them a bunch of tests, Part 2: Pits and gaps

What I learned from last year’s round of language assessments is that our students really do have gaps- the challenge is that their gaps are incredibly varied in depth and content area. How do we quickly identify where those gaps are and get students to flourish right out of them? While I’m at it, the greater challenge is figuring out how to add to our students’ storehouse of words and at the same time celebrate the fact that, Hello? They speak (at least) two languages! That’s amazing!

This is part 2 of a 2-part post.

Kids need a climbing rope.

Knowing what to do when you get stuck is just as important as knowing the right answers.

There were students this year who spent entire days in my classroom, because the time allocated for them in their usual class just wasn’t enough. Most of us will empathize with a student who needs an extra hour or so to work through a high-stakes essay question. But by the third hour, and the seventh hour, it gets painful. Are a few of these students trying to get out of class? Sometimes. Have they memorized every curtain, every poster frame in my classroom while they stare off into space and wonder what to do next? Probably. Are there a few who wreak havoc with their neighbors while they alternate between pencil-tapping and cat naps? Ugh. Totally, yes. Was there any learning happening between hour one and hour five? Not usually.

What I noticed about a few dozen of the teenagers who made their home in my classroom to make up standardized tests last spring was that, contrary to the far-away look in their eyes, they really were trying hard. (Coincidentally, on our school’s California Healthy Kids Survey, most of them report that they try to always to their best in school. In turn, I’ve watched their teachers reel in their seats and ask, Are you kidding me? You guys spent the whole class period trying to unblock video games!) They just happened to come to a question they couldn’t answer, and felt paralyzed.

Education researcher James Nottingham has built a tome of resources explaining how to prepare students for what he calls “The Learning Pit”. They need to know what it feels like to not know the answer. But more importantly, they need to know what to do to get themselves out of that “pit”. Similarly, in John Hattie’s Visible Learning Protocol, teachers ask students, “What do you do when you get stuck?” (Handy video example here.) As adults, I’d like to think we grow more comfortable with not knowing everything, and the most well-adjusted of us grow equally comfortable with knowing how to move forward from those “pits”. Teaching kids how to get un-stuck is like throwing them a rope they can use for the rest of their life. And it might make test-taking a little less brutal, too.

Language support classes are not a punishment.

I will always have a bias in favor of the arts. I want more people exposed to more visual and performing arts, in the highest quality and quantity that our tax dollars can buy. As school budgets shrink, however, arts can be luxury only afforded those students who don’t need an academic support class. When I see long term English learners enrolled in language support classes for year after year, our “support” seems like an arbitrary punishment. It takes a proficient score on the California state language exam (ELPAC) to exit language support class and free up their schedules for a more engaging elective.

The students I work with have plenty to say to their friends, and have very few qualms with gabbing their way through instructional minutes. They are just as likely to dole out polite “pleases” and “thank yous”, or mouth off to an adult, as their monolingual peers. These are the students whose teachers look up from their rosters and say, “Her? I’ve had her all year; I thought her English was fine.” Until a student is asked to discuss very specific situations in a language test, it can be difficult to see that they actually are operating around language gaps.

Most of the teenagers at my school have been navigating California public schools for years, and in their daily conversations, they rarely miss a beat. It’s “school words”, however, that have them stumped. When asked to justify an opinion, or summarize an academic presentation, an otherwise chatty kid will awkwardly spurt and stumble their way through choppy sentences. I recognize their technique because it’s something I do when I don’t know a word in Spanish: say about six basic words to describe the one more precise word I haven’t learned yet. And maybe point or act it out. I also recognize the apologetic grin and the way they shake their head after their roundabout way of describing something, because it’s the same move I make when I can only get part of my point across in Spanish, my beloved but obviously-second language.

To paraphrase Sir Ken Robinson, an education that goes beyond teaching young people only from the neck up is more crucial than ever. (And it’s just more fun. More of that, please.) Arts classes are not mutually exclusive of language support, but master schedules will often allow for only one or the other. What I learned from last year’s round of language assessments is that our students really do have gaps- the challenge is that their gaps are incredibly varied in depth and content area. How do we quickly identify where those gaps are and get students to flourish right out of them? While I’m at it, the greater challenge is figuring out how to add to our students’ storehouse of words and at the same time celebrate the fact that, Hello? They speak (at least) two languages! That’s amazing!

Challenges aside, I did not realize until spending twelve minutes at a time (the task was repetitive- we got really good at our timing) with lots and lots of bilingual middle schoolers that my teacher assumptions were wrong. By casual observation, I couldn’t catch what a standardized test set out to measure- there really were places they were “stuck” with their English. Support classes are not a punishment, they are actually intended to fulfill a need. We need to do right by those students, so they can get out there and write some killer proposals for their next art project.

If you find standardized tests a bore, don’t worry- we all do. But if you look closely, there’s a lot to learn from the young humans who muscle through them every year.

Re-posted with love and permission from The Napa Wife.